The Power of the Narrative in the 2020s

Museum of Arts and Design. Jewelry Stories: Highlights from the Collection 1947–2019. Edited by Barbara Paris Gifford. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2021.

Published in conjunction with the exhibition 45 Stories in Jewelry, Jewelry Stories: Highlights from the Collection 1947–2019 offers a visual as well as literary feast. It celebrates the art jewelry collection of New York’s Museum of Arts and Design (MAD). (MAD was formerly known as the American Craft Museum [ACM]). Together, the show and the book provide a powerful reminder of the riches in one of the oldest and most revered American public collections of contemporary craft.

On one hand, with their emphasis on post-1947 jewelry and adornment, both exhibition and publication demonstrate the silo approach that dominates recent scholarship within contemporary craft. Encouraging the examination of one aspect of the crafts rather than the entire subject, this tactic usually results in an in-depth study of a particular field or medium by tapping into its specific role within the history of decorative arts and design.

In recent years, this strategy has proved especially rewarding because it allows a much-needed focus on diversity, identity, and gender-related issues. All are addressed, in different degrees, in this exhibition and publication. However, this approach prevents and/or limits discourse about the context of such objects within the larger framework of the art of today.

Unfortunately, many of the works featured in Jewelry Stories are considered only from the perspective of twentieth- and twenty-first century craft and design. Interestingly, those texts that do reference parallel developments in modern and contemporary art largely were prepared by art historians of a similar generation and/or training.

The premise of Jewelry Stories is established in the foreword by MAD’s board chair, Michelle Cohen, who deserves special recognition for her support of this project. Cohen unequivocally claims that every piece of jewelry—be it a traditional form composed of precious stones or a more contemporary example that uses unprecedented materials—has a story. However, since MAD’s holdings date from 1947 onward, the reader will never be able to learn how stories about works made prior to that time compare.

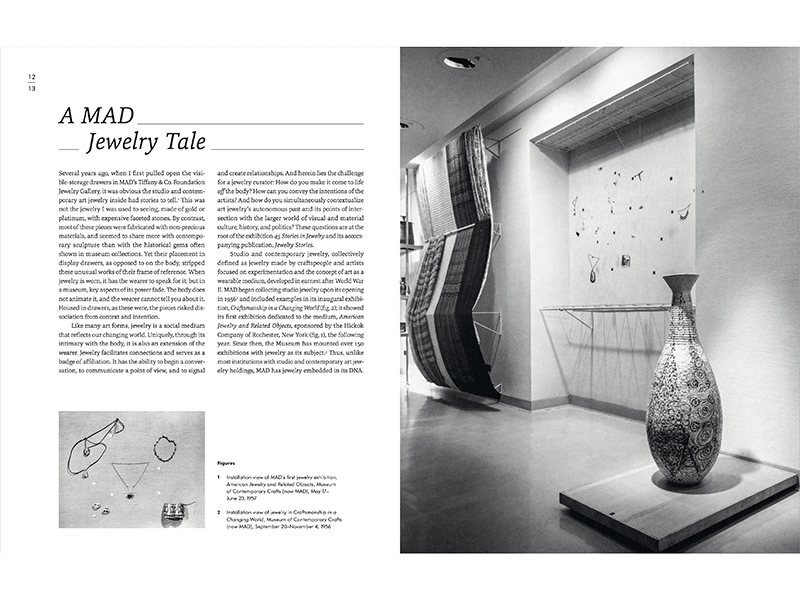

Cohen’s foreword is followed by a brilliant essay entitled A MAD Jewelry Tale, by MAD’s associate curator and publication editor, Barbara Paris Gifford. In an informal tone, Gifford first carefully outlines the project. She then draws upon MAD’s jewelry holdings to recount the dramatic story of the innovations and innovators behind international art jewelry from the post-war period to today.

Gifford traces the shift from the focus on abstraction and Modernism of the late 1940s and 1950s to experimentation, first with materiality and then with various forms of technology, including digitization. All the while, she focuses on the transformations of the body’s role within contemporary jewelry. Gifford clearly spells out the accompanying aesthetic revolution, too, from jewelry that responds to traditional concerns to pieces that provide commentary on social, political, cultural, or environmental issues.

Among the most satisfying aspects of the essay are Gifford’s efforts to integrate new research. Her ability to combine the specific contributions of the numerous players, put them in context, and gather this information into a compelling, beautifully crafted document makes her essay an invaluable contribution to the literature in the field. Its value is diminished only by the author’s choice to relegate her definitions of studio, contemporary, and art jewelry to an endnote.

The exhibition and book integrate the voices of multiple contributors into a monumental collaborative effort. This brings to mind the “scientific committees” made up of scholars who, when blockbuster shows were first introduced in America in the 1960s and 70s, were told to develop their exhibition “narratives.”

Essentially, MAD’s project combined efforts by both Gifford and project manager/MAD assistant curator Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy with those of a committee. It consisted of seven highly respected educators, curators, writers, and historians in the field as well as countless esteemed advisors. Ranging from the talented artist and educator Timothy Veske-Mahon to New York Jewelry Week co-founder Bella Neyman, committee members assisted with the initial selection of objects. They then contributed texts on select artworks. Its members also were asked to evaluate MAD’s jewelry collection, identifying areas for potential growth. Finally, they also suggested additional authors who, like the committee members, prepared narratives that reflect their particular practice.

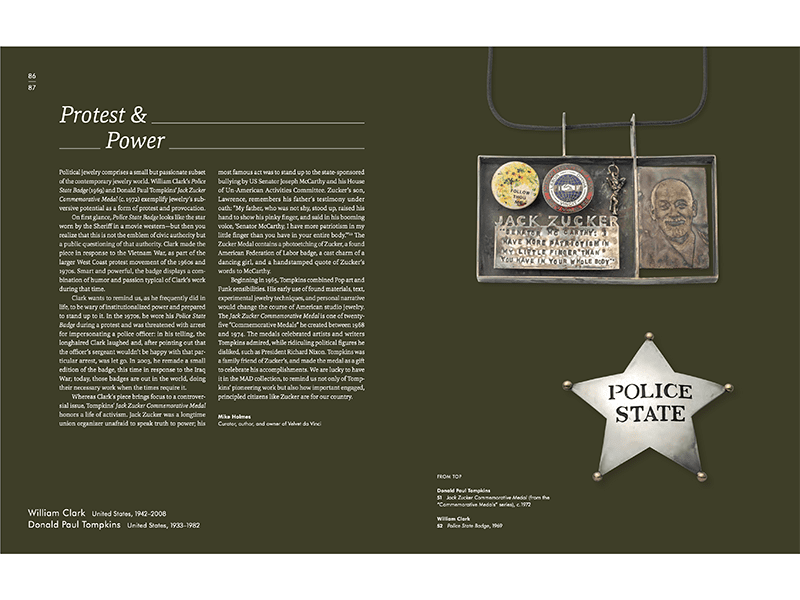

The resulting essays, used in an abbreviated form in the exhibition, are rich, lively, and informative. They inspire both the reader and the exhibition viewer to pore through large amounts of text. The essays are grouped by theme based on the stories told by the artworks. There is, however, no formal introduction to each topic. Some stories focus on a single artwork, others on multiple objects by the same art jeweler. Finally, there are a few where several seemingly different objects are presented together. Authors such as Donna Bilak and Urmas Lüüs skillfully unveil the similarities between these works while capturing the magic of making.

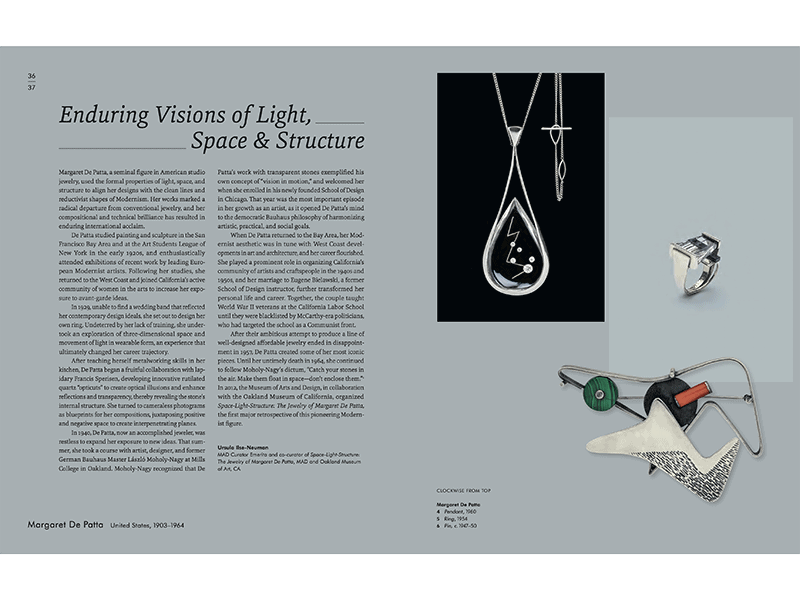

Some authors, such as MAD curator emerita Ursula Ilse-Neuman, curator Elizabeth Essner, and curator and editor of First American Art Magazine America Meredith (Cherokee Nation), have chosen the more traditional biographical approach. It places commentary on MAD’s works within the context of artistic careers and oeuvre. Other writers, such as platform and magazine Current Obsession founder Marina Elenskaya, provide novel, thought-provoking cultural interpretations.

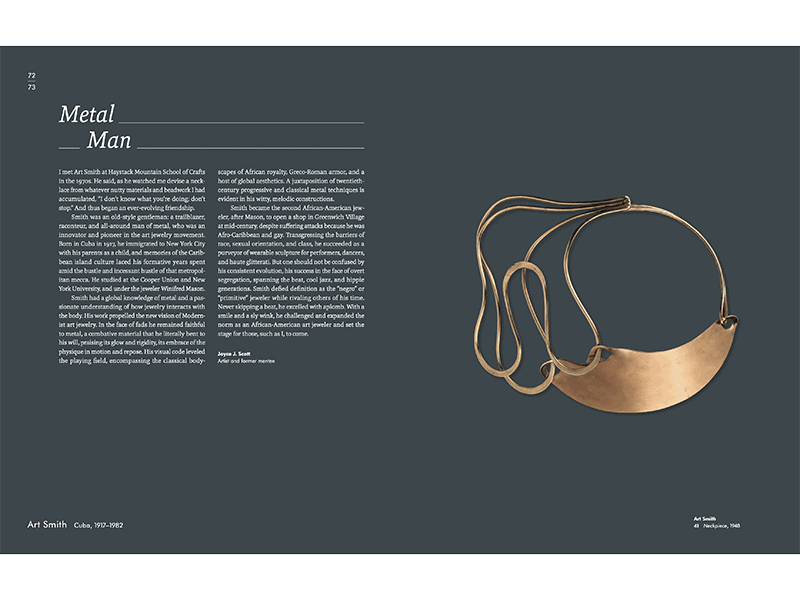

Several narratives are particularly moving. They include Dr. Joyce J. Scott’s inspirational essay on African American Modernist jeweler Art Smith; Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy’s stirring narrative, using works of Mexican artist Aline Berdichevsky and American art jeweler Julia Turner to describe the perils facing immigrants today; and Helen W. Drutt English’s account of the Stanley Lechtzin story. What Drutt English writes, for example, can come only from a sensitive scholar who has watched an artist grow over a lifetime. Likewise, American artist Thomas Gentille’s tribute to his teacher and mentor John Paul Miller gives new perspective on both artists. It makes the reader wish for additional scholarship.

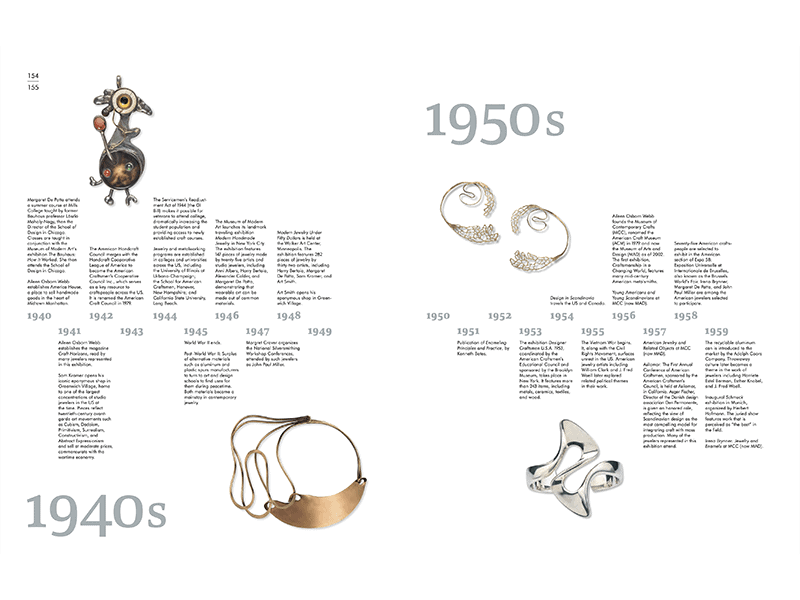

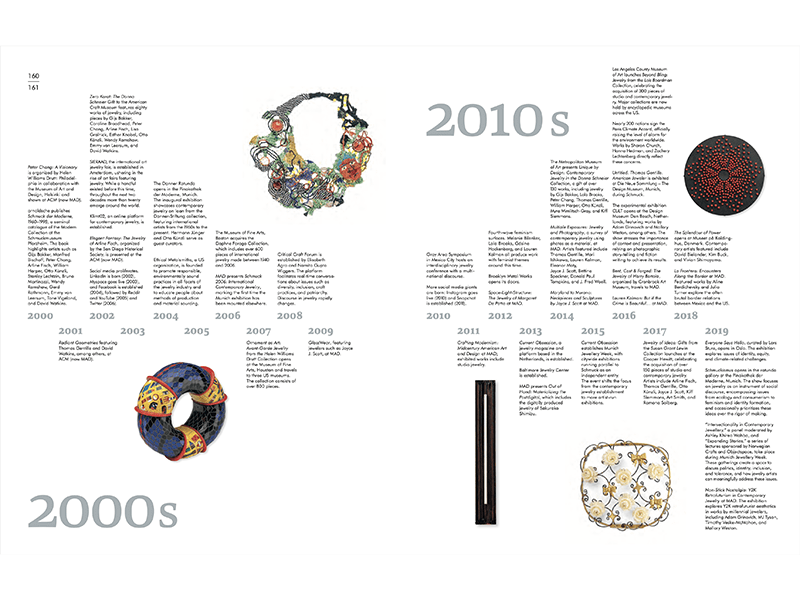

The book contains a selected bibliography for the featured artists. A “Selected Chronology,” covering the years 1930–2019, is also included in both the publication and the exhibition. Gifford claims it to be largely “US-centric,” reflecting the museum’s original commitment to American craft. However, key international moments in art jewelry and technology are also included. Nonetheless, the recent events generally are those organized by MAD and other New York institutions. Or else they reference occurrences in which the various contributors to the project participated. This is somewhat off-putting. It raises the specter of the art world’s well-known colloquialism that “Nothing happens west of the Hudson.” Also, the descriptions of those events peripheral to the history of ACM and MAD often do not describe their true importance within the field.

Despite these criticisms, the book Jewelry Stories is well organized, beautifully designed, and richly illustrated. It is a visual delight to flip through. The narratives are each paired with stunning, full-page color plates of the jewelry. The work has been exquisitely photographed off the body to show how each piece would be exhibited in a museum setting. In a few instances, additional photographs present the objects being worn to reinforce the narratives.

Today, storytelling plays a critical role in making sense of artworks of all media and from all ages. In fact, it is now the buzzword for museums in general. Essentially, it is what art historians have been doing for ages—researching the artist/maker, the meaning of the work, and its origin and place within social and cultural history. Museums now, however, are finding that audiences cannot get enough of this approach. In 2020, when 45 Stories in Jewelry opened at MAD, the museum received much praise for its innovation. Even though the pandemic lowered museum attendance, this effort, along with its accompanying beautiful book, reinforce the uniqueness and importance of art jewelry for a broader audience.

Note: 45 Stories in Jewelry was shown at MAD from February–April 2022. It closed briefly for renovations to the second floor galleries and re-opened as Jewelry Stories in July 2022.